Curbing Student Stress can Lead to Grade Inflation, Watch Out!

- Jan 3, 2025

- 3 min read

The natural tendency of man is that everyone is happier when they are successful. Within the school setting, happiness often equates with good grades. The questions by researchers in recent days are: “Is the grading framework within our educational system beginning to produce a skewed view of student performance?” “Are teachers too swiftly handing out good grades in order to avoid both student and parent stress and conflict?”

In a recent study performed by Doug Lemov, a distinguished author on education, statistical data over the last 10+ years show that although student GPA has significantly increased in 2016 in all the four core subject areas of English, Math, Science, and History, the national ACT score averages have remained relatively stagnant. If students truly are performing higher at school and earning better grades, then why has the national average of standardized achievement tests not increased?

One potential solution to this mystery is the newfound and popular view of child stress. Within the last five years, educational studies like this one from Healthline suggest that giving students more than ten minutes of homework per subject will lead to abnormal levels of stress and likely harm their development. Other studies say that teachers and parents need to begin “to improve upon the social and emotional skills of preschool aged students…not waiting until they are in elementary or high school.”

And so, this heightened sense of attention to student stress has quickly turned many classrooms into utopian environments in which both average performances and learning flaws are applauded. And yet, a deeper dive into the reality of stress, and both its positive and negative effects on life, is needed.

A recent book entitled “The Upside of Stress”, written by Dr. Kelly McGonigal, a research psychologist at Stanford University, helps contrast the paradigm of both positive and negative stress in the classroom. Early in her career, Dr. McGonigal gave presentations on how to mitigate stress in the lives of Stanford college students. And yet, as her research developed, she found that the stress tests often used to gain the statistical data that represented “bad stress” often included things like throwing rats into a bucket of water before they nearly drowned, pulling them back out again, and repeating the process over and over. Naturally, under those types of circumstances, the experienced stress is toxic. But these types of tests are not a great comparison to the type of stress that a student may face while studying for an exam.

When considering the reality of stress, one must remember that the people who thrive are not people who live without stress. In fact, successful people are often those who live with stress, but possess an effective mindset on how to deal with stress. Dr. McGonigal says in her book, “It’s impossible to have a meaningful life without having some stress.”

She even connects the surge of mental health issues nationwide to the fact that children are not facing regular exposure to rigorous academic deadlines and assessments that build a positive form of stress. In many cases, stress can often mobilize self-confidence after putting the work in to prepare.

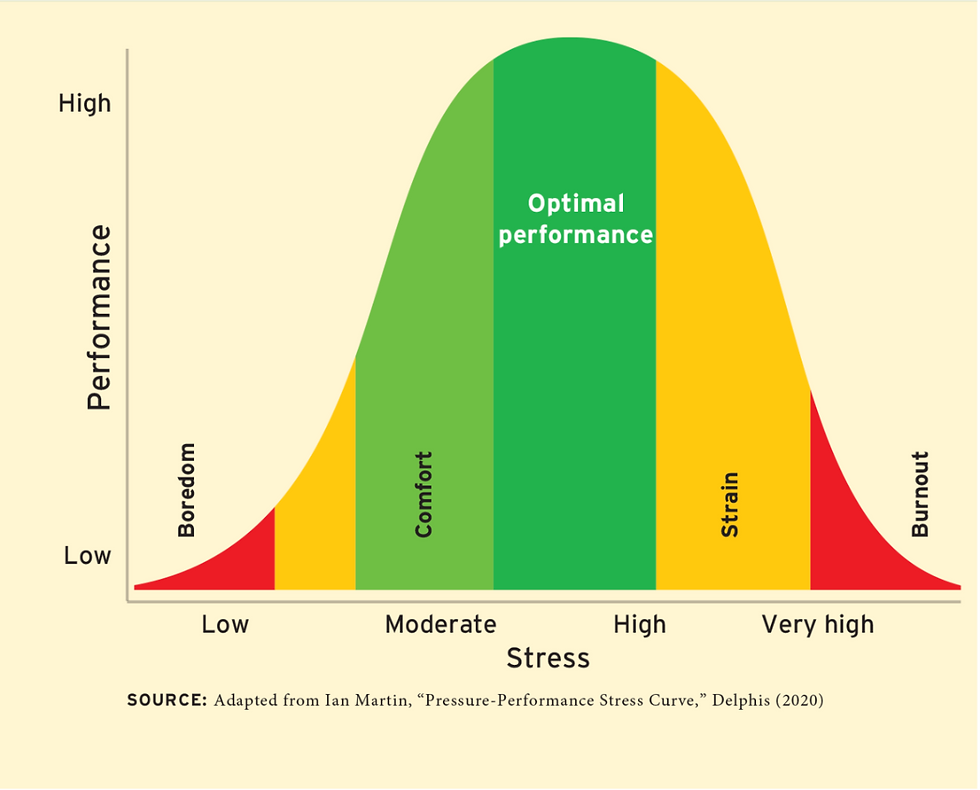

The Yerkes-Dodson Curve illustrates how the relationship between stress and performance is not linear: Performance increases as stress rises from low levels, and then falls off when stress becomes excessive.

In the school setting at BBCS, we encourage our teachers to evaluate the ability and needs of the students within their classroom, and then push them to the maximum balance of both academic rigor and reasonable expectations. Exam week at the end of each semester should come with a moderate level of stress that pushes students to challenge themselves more than the average week. This type of extra pressure helps to prepare them for situations in the future workplace as adults when there is a need to stay late, meet harsh deadlines, or develop strategies that require extra planning.

If our classrooms and grading systems lack rigor and assessment credibility, we are doing a disservice not only to the higher learning institutions, but also to our students who will one day be faced with challenges that require perseverance to be successful. Pray with us as we daily seek to find the proper balance between grace and austerity to help prepare our students to be the best that they can be!

Written by Jon Knoedler, BBCS Administrator

Comments